· Excerpt

· Editor’s Comments

· Reviews

· Find Out More

· Locate a Copy

Excerpt, from “Lust and Leprosy”

Here, then, is the plot [of Gabriele D’Annunzio’s The Crusade of the Innocent (La crociata degli Innocenti)].

The dramatis personnae are five, with names sonorous and pregnant with symbolical significance: Odimondo (Hate-the-World), a young man; Novella (New-Girl), his passive adorer; Gaietta (the Cheerful One), his infant sister; The Mother, anonymous genitrix of Odimondo and Gaietta; Vanna la Vampa (Johanna-the-Blaze or, shall we say, the Vamp), the contaminated, but ever-pure-at-heart enchantress; a mysterious Pilgrim, plus a Celestial Chorus and White Voices. Even in the list of characters one must make allowances for poetic imagery.

Act I. Place: A dismal swamp, in which rises (geological license) a huge rock full of cavernous recesses; at right, a chuch (architectural license); in a “breath of gold” — which is the miasma rising from the dismal swamp — are heard the noises of innumerable birds, the dirge of snipes “which whimper like juvenile gnats” (insectile license), and the twitter of “divine buzzards” (ornithological license). Time: That melancholy, crepuscular hour, you know, Saturday before Palm Sunday, 1212.

New-Girl is doomfully sitting in the swamp by a cattle-trough which, as always in Italy, is a Roman sarcophagus. (Why a watering-trough in the midst of water? But don’t ask embarassing questions.) Enters Hate-the-World, carrying a horribly heavy little bundle of olive sprigs. The bundle is heavy, as New-Girl soon discovers by thrusting into it her hand, which collides with an icy little foot, because it contains the corpse of the Cheerful One. For Hate-the-World has just cut the throat of his infant sister, fortunately before the rising of the curtain….

Act II. Dewy sunrise, though the “bluish darkness is as silent as at the bottom of the sea.” The mysterious Pilgrim, emerging from the thick timber, approaches the doomful tower and instinctively makes for Johanna, the still much-lepered Vamp….

Act III. Front stage: One of the many boat loads of mystic infants sailing on their voyage to the Holy Land. They are packed “as a herd doomed to slaughter,” and though tortured by hunger, seasickness, and vermin, they are full of heroic fortitude and still singing…. Hate-the-World, who happens, for no reason at all, to be on deck too, has been lashed to the mainmast by the jealous sailors for casting amorous glances at the still beautiful, though pure, ex-leprous enchantress….

Act IV. Two of the infant-laden vessels are wrecked on the rocky shore of a deserted island. The shore, the decks, the sea as far as naked eye can penetrate, everything is bestrewn with innumerable defunct babes. Hate-the-World is again carrying the heavy corpse of his infant sister, the Cheerful One. “It seems,” says the uncertain author, “that in his delirium he has sacrificed her once more.” He was pure again and now he is again guilty, so, according to this subtle symbolism, he must again carry the heavy burden, and Sister must again have that wicked wound in her intermittently molested jugular vein….

… [D’Annunzio] must have been convinced, judging from his words, that this play was full of high emotion. Emotion without restraint, and that is the trouble, without that artistic restraint which Dante called “il fren dell’arte,” and Babbitt “the inner check.” D’Annunzio was far more interested in another kind of check.

Editor’s Comments

Sleuthing in the Stacks collects seven essays by Rudolph Altrocchi, a professor of Italian and long-time member of the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley. Altrocchi describes them as accounts of literary detection, but literary archaeology might be more accurate, for he consistently uncovers layer after layer of precedents behind each piece of “original” work he examines.

Despite Altrocchi’s considerable expertise and serious studies, in no way does he attempt to make any profound claims for this book:

The research scholar who has lots of fun in his bookish hunting also wishes to share this fun. Although he does his happy hunting, he sleuthing, alone, he wants to share his game….

Some might say that in this time of global war [the book was published in 1943] literary research acquires, by comparison, a petty significance. That may well be so. But it also acquires the value of “escape.” The author hopes that this book may be a jolly, bookish escape to readers as it was to him.

“A jolly, bookish escape” is the perfect description of Sleuthing in the Stacks. In each essay, Altrocchi starts with a particular text, usually obscure. In “Handwriting in Search of an Author,” it’s a small collection of poems by one Monsignor Giovanni della Casa, a patrician member of the Florentive clergy from the mid-16th century. The book is filled with tiny marginal notes that the bookseller speculates belonged to a much-better-known poet, Torquato Tasso. He graciously loans the book to Altrocchi, who proceeds to unravel its provenance and then, the rightful source of the notes.

“Now somebody might ask: Why question the authenticity of it at all? Why go to so much trouble?,” Altrocchi admits. But forged handwriting, he explains, is so common that it’s riskier than not to assume authorship without a thorough investigation. His own follows two lines: the handwriting itself, and the content of the notes themselves.

His suspicion was fed by the fact that one Mariano Alberti, a captain in the Papal Guard, had been convicted of forging Tasso’s handwriting in the 19th century. Altrocchi locates the suspect book in the inventory of Alberti’s belongings included in the record of his trial “magnificent folio volumes (oh the grandeur of those Papal days).” Not satisfied, though, he then carefully matches up the notes against those in an authoritative compilation of Della Casa’s works, meticulously commentated, amounting to an “oppressive total of 2018 pages.” He finds that 75 per cent of the notes attributed to Tasso match those written between 1707 and 1728 by one Sertorio Quattromani. The last nail (literally) in the coffin is provided by a chemical analysis, which finds the aged, reddish ink isn’t ink at all, but hydrated iron oxide — the water Vatican authorities found filled with rusting nails in a glass in Alberti’s apartment.

This gloss makes “Handwriting in Search of an Author” sound far too pedantic. Altrocchi lightens every step along the way to his conclusion with wry asides and gentle judgments on all parties. There are no great villains or saints in his world, and after resoundingly demonstrating Alberti’s guilt in forging the annotations, he passes the mildest of sentences: “May his rascally soul and his clever, extremely clever hand rest in peace.”

The other pieces in Sleuthing in the Stacks take similarly esoteric subjects for entertaining rides. In “Lust and Leprosy,” excerpted above, he deconstructs a truly awful bit of kitsch by the Italian poet and proto-fascist, D’Annunzio, and traces its roots in a variety of Catholic miracle plays. In “Where there’s no Will, there’s a Way,” he recalls a play he once wrote with a fellow alumnus in hopes of winning a prize offered by the Harvard Dramatic Club. The play won no prize and was promptly forgotten. But Altrocchi proceeds to unravel the long literary tradition behind its principle dramatic event, in which an heir conspires to gain the rights to his just-deceased father’s estate. He convinces a neighbor who resembles the father to take to the recently-vacated death bed, recite a last will and testament, and then play out a convincing death scene. Altrocchi’s source is none other than Dante’s Inferno, where among the Maleboge (“Evil Pockets”) in the eighth circle of Hell he spots one Gianni Schicchi, who impersonated a rich man and dictated a false will in his own favor. From that source, however, he traces a wealth of derivations, adaptations, and reinventions, concluding:

Wherefore I stopped this line of sleuthing, which make me now stop my discussion. But haven’t I proved how much jollity can come out of Dante’s Hell and from a corpse?

Upon this sleuth, who now feels qualified for the exalted title of “third grade digger” or perennial (through seven centuries) literary undertaker, may the forgiveness come of the reader … (oh no, there is no reader left).

If you Google Altrocchi’s name, you’ll find he’s best remembered on the Internet for his essay, “Ancestors of Tarzan,” which appears in Sleuthing in the Stacks. In it, he uncovers dozens of accounts, reaching all the way from antiquity to contemporary “factual” accounts of jungle life, in which one or more of the essential elements — the abandoned child, the nuturing she-beast (gorilla, wolf, dog, etc.), and the mastery of survival skills and eventual rediscovery — are blended. The ur-story behind Tarzan, he writes,

… survived not because of casual animal foster-mothers, but by virtue of its essential humanity. Young maidens who succumb to passion; secret fruit of their transgression exposed and saved by miracle, surviving through coincidence and adventure for heroic accomplishments in history or philosophy — this is of the very tissue of life, at all times and in all places, and therefore also of literature.

Sleuthing in the Stacks is certainly the “jolly, bookish escape” Altrocchi hoped for. But as each essay proves in its own special way, it’s also a sly and subtle revelation of the depth, breadth, and intricacy of the web of connections that can be found beneath the surface of just about every work of literature, whether great or small, authentic or forged.

Reviews

- · J. T. Frederick, Book Week, 16 July 1944

- Prof. Altrocchi writes so frankly of his hobbies, with so much humor and pleasant personal detail that there is much enjoyable reading in Sleuthing in the Stacks even for the person who knows little or nothing about the field of the researches described.

- · Robert Altick, New York Times, 23 July 1944

- To the unsympathetic bystander these discursive essays might almost represent the reductio ad absurdum of literary source-investigation, but they are nevertheless fun to read. It can never be sufficiently deplored that so few academic men can deliberately write unacademically and get away with it. Professor Altrocchi is carried away in his zeal to be companionable.

- · E. L. Tinker, Saturday Review, 26 August 1944

- The book is full of unlimited scholarly research, and an acute reasoning worthy of Dr. Holmes. It is often very interesting in its breadth of learning with its varied and recondite facts….

Find Out More

- Wikipedia entry on Rudolph Altrocchi

- You can find a brief biography of Altrocchi at “Guide to the Rudolph Altrocchi Papers” from the University of Chicago Library Special Collections Research Center.

- After a long and distinguished career as a neurologist, Altrocchi’s son Paul Hemenway Altrocchi published his own work about a murky figure from literary history. In this case, his novel, Most Greatly Lived, he recounts the life of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, often claimed as the true author of Shakespeare’s works.

Locate a Copy

Thanks to an enthusiastic boost from San Francisco Chronicle reviewer Joseph Henry Jackson, Sleuthing in the Stacks sold far better than most academic books when it was first printed in 1943. Although it was reprinted in 1968 by the small Kennikat Press, there are still dozens of copies of the original available for as little as $5 from online dealers.

Antoine left with two stretchers, their bearers silent. They went on foot. In the depot at night you have to watch where you put your feet. The ground is full of traps and pitfalls, switch heads, ditches, and engines under steam, a tiny wisp of smoke coming from their stacks. Antoine was thinking. He did not take such deaths very easily. People said, “Accident at work.” And they tried to make you believe that work is a field of honor, while the company provides the widow with a pension, a niggardly pension, it parts with its pennies like a miser, it thinks that death is always overpaid; later it hires the sons of the dead and all is said.

Antoine left with two stretchers, their bearers silent. They went on foot. In the depot at night you have to watch where you put your feet. The ground is full of traps and pitfalls, switch heads, ditches, and engines under steam, a tiny wisp of smoke coming from their stacks. Antoine was thinking. He did not take such deaths very easily. People said, “Accident at work.” And they tried to make you believe that work is a field of honor, while the company provides the widow with a pension, a niggardly pension, it parts with its pennies like a miser, it thinks that death is always overpaid; later it hires the sons of the dead and all is said.

There’s a limit to this respect, though. In fact, we find that horses may have formed a bit too much of Amos’ perspective:

There’s a limit to this respect, though. In fact, we find that horses may have formed a bit too much of Amos’ perspective:

“Mitchell [was] a North Carolinian who became a New Yorker. He went straight from the University of North Carolina to a New York newspaper [The New York Herald Tribune–ed.]. First a reporter, he quickly turned into a feature writer, and then he became an essayist, the best in the city. [He joined the staff of

“Mitchell [was] a North Carolinian who became a New Yorker. He went straight from the University of North Carolina to a New York newspaper [The New York Herald Tribune–ed.]. First a reporter, he quickly turned into a feature writer, and then he became an essayist, the best in the city. [He joined the staff of  The other five are a kind of writing for which there is no name. Each tells a story, and is dramatic; each is both wildly funny and so sad you can hardly bear it; each tells its story so much in the words of its characters that it feels like a kind of apotheosis of oral history. Finally, like the Icelandic sagas, each combines a fierce joy in the physicality of living with a stoical awareness that all things physical end in death, usually preceded by years of diminishment. One winds up admiring Mitchell’s characters (all real people), loving them, all but weeping for them, maybe hoping to live as gallantly.

The other five are a kind of writing for which there is no name. Each tells a story, and is dramatic; each is both wildly funny and so sad you can hardly bear it; each tells its story so much in the words of its characters that it feels like a kind of apotheosis of oral history. Finally, like the Icelandic sagas, each combines a fierce joy in the physicality of living with a stoical awareness that all things physical end in death, usually preceded by years of diminishment. One winds up admiring Mitchell’s characters (all real people), loving them, all but weeping for them, maybe hoping to live as gallantly.

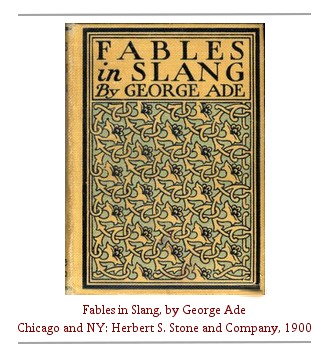

I don’t blame Dreiser for a second, and I understand why he was so hurt when he was accuseed of plagiarism. What he said in substance was that no one ever had described a fast operator so well, and no one ever would describe one so well, so it made every kind of sense to use these marvelous words, and he was simply paying George Ade the sincerest of compliments. Besides, they were both from Indiana….

I don’t blame Dreiser for a second, and I understand why he was so hurt when he was accuseed of plagiarism. What he said in substance was that no one ever had described a fast operator so well, and no one ever would describe one so well, so it made every kind of sense to use these marvelous words, and he was simply paying George Ade the sincerest of compliments. Besides, they were both from Indiana….

Starting out as a realistic novel,

Starting out as a realistic novel,

To keep the Fortnightly subdued and reassuring in tone was comparatively easy. But to lower himself to the temperature necessary to the comfort of his guests in Park Lane taxed Harris sorely. Yet, with a Royal Duke at his table, some measure of restraint was obligatory.

To keep the Fortnightly subdued and reassuring in tone was comparatively easy. But to lower himself to the temperature necessary to the comfort of his guests in Park Lane taxed Harris sorely. Yet, with a Royal Duke at his table, some measure of restraint was obligatory. Close on now —must be. they’d be getting tea ready at home. Had they his field card yet? Fulshaw’s eyes were brilliant with excitement. The first birthday he’d missed at home. They’d send him some of the cake in his next parcel. Must stick near Jack. One up the spout … make sure his safety catch was off. What an uproar. Good job they didn’t know at home exactly what was happening.

Close on now —must be. they’d be getting tea ready at home. Had they his field card yet? Fulshaw’s eyes were brilliant with excitement. The first birthday he’d missed at home. They’d send him some of the cake in his next parcel. Must stick near Jack. One up the spout … make sure his safety catch was off. What an uproar. Good job they didn’t know at home exactly what was happening.