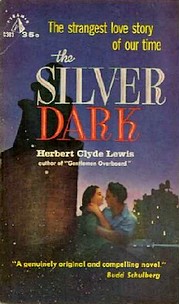

This book is a bit of a mystery. My copy, a 1959 Pyramid Books paperback, shows no prior publication history. There is a quote from Budd Schulberg (“A genuinely original and compelling novel”) on the cover, which is the sort of thing one might expect to be carried over from an original hard cover release–but this appears to be the first and only edition. And there is the fact that Herbert Clyde Lewis died from a heart attack in 1950, which makes this a posthumous first-time publication–something that’s also a little unusual in a cheap paperback.

However this came to be published, it did little to revive Lewis’ reputation. His three other novels–Gentleman Overboard, which I reviewed here a couple of months ago; Spring Offensive, an anti-war novel from 1940; and Season’s Greetings from 1941–were already long-forgotten by then. The Silver Dark

soon disappeared, too. I could locate less than a handful of copies for sale on the Internet today and virtually no library has a copy.

It’s a real shame, for The Silver Dark

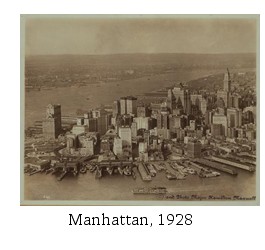

It’s a real shame, for The Silver Dark is a memorable story told remarkably well by Lewis. Theodore Huber is a dwarf, living alone in a small Manhattan apartment, working as a bookkeeper, shuffling through the streets trying to avoid the looks of pity and disgust. The emptiness of his life rings in our ears:

He ate with automatic movement, spoon from plate to mouth and back to plate again. He had no chance for happiness. He was trapped. He was tired of living and unable to die. He was in a void; he was existing in a vacuum. Slowly, he got up and carried the half-empty dishes into the kitchen for Mrs. Asgood to wash in the morning. Time had stopped, as far as he was concerned. For the rest of his life he would feel the same way, think the same thoughts, do the same things every day and every night. He would go on like this. He would observe his fortieth birthday and his fiftieth birthday in this fashion, and then his hair would grow gray and his breath would come short, and one day, alone, he would die a natural death.

His only real interest is in the lives of the beautiful women and handsome men he sees in the streets and through apartment windows. Theodore is not a peeping Tom, but he is at least a glancing Tom. He fantasizes about the lives they live: “She worked in a department store, and now she was hurrying home to her man, who worked in a bank. He was waiting for her, and as soon as she came in they kissed each other. Theirs was not a passionate kiss; theirs was a friendly kiss. Everything they did was friendly, easy, companionable.”

One night, he goes up to the roof of his apartment building to look out at the city. He sees a man and woman in an apartment and watches as they begin to make love. Suddenly, he becomes aware that someone else is up there with him. He panics, but then a strange, misshapen woman sees him, screams and faints. He carries her to his apartment. She revives in a few moments and runs out into the hallway in fright.

He hears no more of this, but over the next few days he starts ruminating, turning the incident over and over. He convinces himself that this woman is his only chance, the one woman who might actually accept him. He tracks her to a neighboring apartment and learns her name–Jane Liste. He decides to write to her. It’s the kind of letter a novice stalker might write: “I have very few friends, in fact, I haven’t any, and you were the first person I talked to, outside of business hours, in a long time…. I’ve been thinking it would be good if we could see each other, because we hardly know one another and might have a lot to talk about.”

A reply arrives. It’s polite, a little friendly. But there’s a hitch. Jane left New York, where she’d been visiting an aunt, the day after the scene on the roof, and returned to Bakersfield, California. A few more letters are exchanged–still friendly, but no more. Theodore, however, manages to talk himself into a romantic whirlwind. He quits his job, put his few belongings in storage, and flies off to Bakersfield. (In Lewis’ world, by the way, there are direct flights from New York to Bakersfield.) He has decided that he and Jane must get married.

Jane, a hunchback who leads an even more isolated life, lets Theodore into her apartment, and an hour or two later, they head off to City Hall for a marriage license. It’s a mark of Lewis’ skill that he manages to make this implausible sequence of events believable. I think it’s due in part to the jarring contrasts he creates. On the one hand, everything going on in the world around these two people is mundane, muted. On the other, there are their emotional worlds, which are filled with bone-aching loneliness and wild dreams of idealized love. While other people go on about their lives, Jane and Theodore are so used to living in pain that it seems sensible to take each other’s hand and go leaping off a cliff into marriage.

It’s not an easy landing, though. One thing they have learned and internalized from decades of living in a world full of normal looking men and women: a deep, deep disgust for people who look like–well, they do. They both want to find not just companionship, but romantic, sexual love; what they feel at the sight of their naked bodies, though, is repulsion.

How Jane and Theodore get beyond these feelings and come to discover a genuine, mature love involves yet more implausible events, but to the very last page, Lewis does a remarkable job of pulling us along and leading us through their emotional transformations. The Silver Dark reminded me at times of McDonald Harris’ Mortal Leap, another book about making a radical life decision. Our rational mind keeps whispering, “This just doesn’t make sense,” and yet we keep turning the next page and reading on.

Coming across a book like The Silver Dark is what makes the pursuit of neglected books so enjoyable. I had essentially no information whatsoever about this book, aside from the fact that I had enjoyed Lewis’ first novel, Gentleman Overboard. I had no idea if this would be good or bad, interesting or tedious. So if it hooked me, it had to do so solely on its own merits, without the aid of reputation, reviews, or anyone’s word of mouth.

And it did. I finished The Silver Dark in three days of a working week, which is exceptional for me. I wouldn’t call it a great novel, but it is certainly a good one–original, unusual, and continuously interesting. It proves once again what treats lie in store for those who dare to dive deep into the stacks.

the book itself or the fact that it was published by the Princeton University Press. Purportedly the “twenty-five year record of ‘the finest aggregation of men that ever spent four years together at Old Nostalgia'” as penned by the class secretary, “Tubby” Rankin,

the book itself or the fact that it was published by the Princeton University Press. Purportedly the “twenty-five year record of ‘the finest aggregation of men that ever spent four years together at Old Nostalgia'” as penned by the class secretary, “Tubby” Rankin,

I picked up

I picked up

tells the story of a confrontation between whites and Native Americans to which neither journalism nor scholarship could possibly do justice. The novel takes place in South Dakota in the 1970s, when local developers start the short-lived Bones War while building a golf course on an ancient burial ground. The American Indian Movement is at its height, government authorities feel under constant siege, the U.S. appears on the verge of living up to its ideals or of falling flat on its face; Michael Doane uses this real-life civil strife to illuminate the individual troubles, and principles, such rebelliousness brings to the fore….

tells the story of a confrontation between whites and Native Americans to which neither journalism nor scholarship could possibly do justice. The novel takes place in South Dakota in the 1970s, when local developers start the short-lived Bones War while building a golf course on an ancient burial ground. The American Indian Movement is at its height, government authorities feel under constant siege, the U.S. appears on the verge of living up to its ideals or of falling flat on its face; Michael Doane uses this real-life civil strife to illuminate the individual troubles, and principles, such rebelliousness brings to the fore….  Thumbing through issues of

Thumbing through issues of  Possibly so; and it may be my fault that they don’t seem to notice there was no way for him to behave well. He had only a choice of behaving badly in different ways. What I mean is that like is like that. Many of the most admired moral examples really will not stand close and logical examination. It is so in the nature of things. Human beings are inevitably in an appalling predicament between their emotions and their obligations; the two elements are not even conveniently distinct, but inextricably snarled in a cat’s-cradle. And the more you try to untable it the worse it becomes.

Possibly so; and it may be my fault that they don’t seem to notice there was no way for him to behave well. He had only a choice of behaving badly in different ways. What I mean is that like is like that. Many of the most admired moral examples really will not stand close and logical examination. It is so in the nature of things. Human beings are inevitably in an appalling predicament between their emotions and their obligations; the two elements are not even conveniently distinct, but inextricably snarled in a cat’s-cradle. And the more you try to untable it the worse it becomes. He married twice. The first time, he was undecided between two sisters. His personal preference was for the younger and prettier of the two; one may assume he was in love with her. But out of sheer altruism, he felt it would be invidious to leave the elder and plainer sister slighted. So he married the elder. It is not known whether the younger was in love with him. She might have been. He was a man of charm, wit, and general attractiveness. And if the younger girl was in love with him, I can’t make up my mind–I am very fond of him–which of the two girls had the best right to murder him on the spot. Both of them, in my opinion, had every right to do so. He had injured the girl he loved and insulted the one he married.

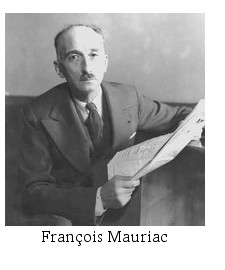

He married twice. The first time, he was undecided between two sisters. His personal preference was for the younger and prettier of the two; one may assume he was in love with her. But out of sheer altruism, he felt it would be invidious to leave the elder and plainer sister slighted. So he married the elder. It is not known whether the younger was in love with him. She might have been. He was a man of charm, wit, and general attractiveness. And if the younger girl was in love with him, I can’t make up my mind–I am very fond of him–which of the two girls had the best right to murder him on the spot. Both of them, in my opinion, had every right to do so. He had injured the girl he loved and insulted the one he married.  Bruce Allen wrote recently to recommend the novels of François Mauriac:

Bruce Allen wrote recently to recommend the novels of François Mauriac: Fortunately for would-be readers, a good deal of Mauriac’s work is in print and easily available for purchase online. All of the above books are in print, as are several less-known works:

Fortunately for would-be readers, a good deal of Mauriac’s work is in print and easily available for purchase online. All of the above books are in print, as are several less-known works:

Not there isn’t any action in

Not there isn’t any action in  It’s particularly noteworthy when one realizes who

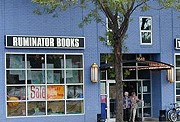

It’s particularly noteworthy when one realizes who  The story of Hungry Mind/Ruminator Books is a parable of how far a passion for books can take you … until simple economics kick in. David Unowsky, who founded his independent bookstore, Hungry Mind Books, near the campus of Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1970, and it acquired a reputation as one of a handful of truly great American bookstores. In the mid-1990s, he and his wife, Pearl Kilbride, along with other partners, started up an independent press, also known as Hungry Minds Books. Over the course of its nearly ten years’ existence, the press published 50 titles, with an emphasis on literary fiction, nonfiction and poetry, including a series of reissues of quality non-fiction under the rubrics of Hungry Mind Finds and Ruminator Finds.

The story of Hungry Mind/Ruminator Books is a parable of how far a passion for books can take you … until simple economics kick in. David Unowsky, who founded his independent bookstore, Hungry Mind Books, near the campus of Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1970, and it acquired a reputation as one of a handful of truly great American bookstores. In the mid-1990s, he and his wife, Pearl Kilbride, along with other partners, started up an independent press, also known as Hungry Minds Books. Over the course of its nearly ten years’ existence, the press published 50 titles, with an emphasis on literary fiction, nonfiction and poetry, including a series of reissues of quality non-fiction under the rubrics of Hungry Mind Finds and Ruminator Finds.

The writing is what makes

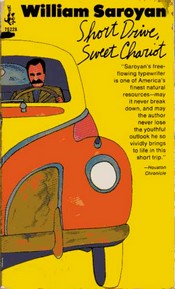

The writing is what makes  “In the summer of 1963 I bought a 1941 Lincoln limousine in New York, so that I might be chauffeur in California to the few remaining dignitaries in my family,” William Saroyan explains at the start of

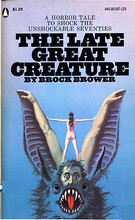

“In the summer of 1963 I bought a 1941 Lincoln limousine in New York, so that I might be chauffeur in California to the few remaining dignitaries in my family,” William Saroyan explains at the start of  movie star of the 1920’s and ’30’s (he’s like Lon Chaney Sr. to the nth degree.) We learn of his fall from fame, and his attempted comeback in the phantasmagorical year of 1968. In his prime he made “Ghoulgantua”, the most terrifying film ever made (about a combination Frankenstein’s monster/vampire.) He created the famous monster “Gila Man” (a sort of werewolf lizard) during the war. Later he was blacklisted for political reasons, went to Germany to make a legendary, unreleased horror movie about the Nazi concentration camps that was supressed by both West and East Germany, and gradually sank into obscurity. Then low-budget Hollywood came calling with an offer to make a cheap Roger Corman-style Edgar Allen Poe rip-off titled “Raven!”

movie star of the 1920’s and ’30’s (he’s like Lon Chaney Sr. to the nth degree.) We learn of his fall from fame, and his attempted comeback in the phantasmagorical year of 1968. In his prime he made “Ghoulgantua”, the most terrifying film ever made (about a combination Frankenstein’s monster/vampire.) He created the famous monster “Gila Man” (a sort of werewolf lizard) during the war. Later he was blacklisted for political reasons, went to Germany to make a legendary, unreleased horror movie about the Nazi concentration camps that was supressed by both West and East Germany, and gradually sank into obscurity. Then low-budget Hollywood came calling with an offer to make a cheap Roger Corman-style Edgar Allen Poe rip-off titled “Raven!” book, Gardner attempts to hold the high ground against contemporaries such as Bellow, Mailer, and the fearsome nouveau romans of

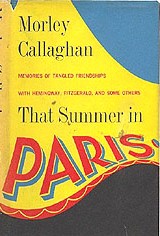

book, Gardner attempts to hold the high ground against contemporaries such as Bellow, Mailer, and the fearsome nouveau romans of  Morley Callaghan is my favorite 20th-century novelist. His

Morley Callaghan is my favorite 20th-century novelist. His  In

In  Gold lived in the same apartment building during one of the worst periods of Cheever’s life, when he was drinking himself to death during a teaching gig at Boston University. Gold, whose drinking problems were slightly more manageable than Cheever’s, had released a short story collection,

Gold lived in the same apartment building during one of the worst periods of Cheever’s life, when he was drinking himself to death during a teaching gig at Boston University. Gold, whose drinking problems were slightly more manageable than Cheever’s, had released a short story collection,  Cheever met Kentfield during a stay in Hollywood in 1959 and the two men had a brief, intense affair that left Cheever paranoid about his homosexual feelings. Kentfield was a former Merchant Marine sailor whose most successful novel,

Cheever met Kentfield during a stay in Hollywood in 1959 and the two men had a brief, intense affair that left Cheever paranoid about his homosexual feelings. Kentfield was a former Merchant Marine sailor whose most successful novel,  Newhouse, who was born in Hungary, started out as a radical novelist whose 1934 novel about the down-and-out,

Newhouse, who was born in Hungary, started out as a radical novelist whose 1934 novel about the down-and-out,