I was intrigued when I can across The Secret

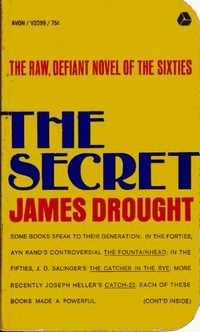

I was intrigued when I can across The Secret in the stacks of a used book store in Seattle. “At long last, something real on the American literary scene; very powerful,” Paul Pickrel of the Yale Review was quoted on the bright yellow cover. “The only trouble with The Secret

is that it makes me feel inferior,” it also quoted from a review by Paul Jennings in the Observer.

Now, I’ve spent many hours scanning through shelves of used paperbacks, so it’s not too often now that I come across something truly new and unknown to me. Naturally, my eyes pricked up at this sight and I bought the book. When I sat down to read it for the first time, however, I quickly grew tired of it and set it aside. That bold banana yellow jacket kept catching my eye, though, and finally this week I sat down and dedicated myself to a discovery of Mr. Drought’s genius.

It was dedication alone that stayed my hand the dozen or more times in the last few days that I felt like hurling this book across the room. This is not a novel. Mr. Drought himself referred it The Secret as an “oratorio.” “Screed” is probably a more accurate term.

If Mr. Drought possessed any genius in this book, it’s of the ilk of that of Dr. Gene Scott or Joe Pyne or the guys I used to run into on the 1AM bus home from downtown after working swings. Here, for example, is Drought’s take on youth’s first realization that success is not all it’s cracked up to be:

For the young, it is like seeing a lovely lady, refined by a fine family, slip out one night in all her silk finery and walk into a woods erect and noble, where suddenly she crouches, rips a bird to pieces and eats it raw, shits in a hole and then kills another refined lady whom she meets at an appointed spot.

It’s that second killing I don’t get. OK, illusion of civilization revealed in its primal barbarity. I get that. But then killing a fellow refinee with whom she’s made a rendezvous? Survey a thousand kids a year out of high school and none of them will come up with that image.

The Secret loosely follows the lines of James Drought’s own life: raised on the outskirts of Chicago, a bit of a loner and rebel. An unsuccessful time in college, then a stint in the Army around the time of the Korean War as a paratrooper. Somewhere in between he meets and marries a beautiful, wonderful woman, and they raise a boy and a girl. He becomes a writer and eventually produces this book, which is intended to reveal to all American youth the secret that the world is out to kill you:

You have to conclude that your country has run amuck, that the people responsible are insane, that you can not trust your leaders, your President, your general, your parents, your friends, your neighbors, you co-workers, your police, your town, your state, your country, anymore because it is liable to turn upon you for no reason at all, except that for its own security it needs a scapegoat, any scapegoat including you, and there is no appeal possible.

The problem, you see, is that virtually everyone Drought’s nameless narrator meets is a shell, a stereotype, a craven one-dimensional drone:

Money was the king in those days; it was the goal for which people used up their lives, it was the prize by which they judged their accomplishments, the energy that made their institutions grown, it was the rationale, the reality, the ring of truth, the religion, it was the one single thing that everyone wanted, respected, cherished, needed, it was the spark, the spirit, the soul of an entire age in America and there was nothing else, no dream that could match it….

It goes on from there, but I’ll spare you the trouble.

Perhaps one of the reasons I found this relentless hammering away at the Great American Myths particularly tiresome was that Drought chose to make his narrator the most insufferably superior being to inhabit a book without the slightest redeeming scrap of humor. Early on, we learn that he and only he is the master marksman and hunter among his fellows:

I found most difficult the very idea I had to accept that my friends could not do these things well, and although I made many excuses for them, soon I had to cease blaming fate and put the blame on their clumsiness, and afterward I could do nothing but smile with boredom as they discussed their theories on how to fish, snare and trap, urging me to try some so they could see if any worked. I shot squirrels out of trees, and I had to admit I was a better shot, either because of a gifted eye, a steadier hand, a determination, or what, but more did fall to the ground, brother, when I shot than fell when my friends fired away hitting limbs, leaves and ticking distant houses, swearing that something was wrong with their goddamn sights, their sleeve caught, something was in their eyes, the gun was bent, etc. so I couldn’t ignore their clumsiness and my skill for long.

Which just goes to prove once more that the one downside to being better than everyone else is that it’s so tiresome having to put up with everyone else’s inferiority. The narrator goes on to tell us that there, along the deserted creeks outside Chicago, he caught or killed “catfish, possum, coon, trout,” “dove, pigeon, a buck, and once on a weekend a deer with arrows, and another time a bear with three arrows.” I can remember guys in junior high school telling whoppers like that. It was always those little details they’d chosen so carefully to impart that final pinch of verisimilitude that tipped you off that it was all a bunch of B.S.. “On a weekend.” “With arrows.” Yeah, right.

Ironically, The Secret proved to be a little American success story in itself, despite its message. Drought first published the book himself and sold it, along with several of his earlier novels, out of the back of his trunk. Eventually, Avon Books offered him a contract and released The Secret

, as well as his earlier novels Mover

, ii: A Duo

, and The Gypsy Moths

in paperback. The Gypsy Moths

brought him greater fame, if still not much, due to the 1969 film version starring middle-aged Burt Lancaster as the hero and very young Gene Hackman as a sidekick.

Whatever else success did to Drought, it seems to have stilled his pen for a good ten years or more. Only in the late 1970s did he emerge into print again, with something called Superstar for president: An American satire–and on his own nickel once again. According to one biographical account, Drought was nominated by some European critics for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1973. Now, according to the Nobel website, nominators can be any of:

- Members of the Swedish Academy and of other academies, institutions and societies which are similar to it in construction and purpose;

- Professors of literature and of linguistics at universities and university colleges;

- Previous Nobel Prize Laureates in Literature;

- Presidents of those societies of authors that are representative of the literary production in their respective countries.

My bet is on those wacky Académie française guys.

Should you care to sample Drought’s work despite the cruel drubbing I just gave it, you can find several of his works online and free to download, thank to the efforts of his children, who established drought.com a few years ago. You will find the texts of The Gypsy Moths (1955), Memories of a Humble Man (1957), Mover: a Modern Tragedy (1959), and, not least, The Secret (1962).

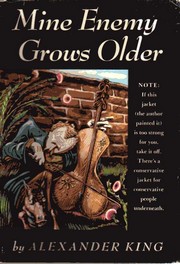

Every writer who’s ever been featured on

Every writer who’s ever been featured on  It was as an illustrator that King’s career finally took off. Throughout the 1920s, he was caught up in the convention-flounting wave of Mencken,

It was as an illustrator that King’s career finally took off. Throughout the 1920s, he was caught up in the convention-flounting wave of Mencken,  My theory is that King’s was a safe form of revolt. He mocked convention, but he didn’t exactly offer an alternative–nor did he suggest that people grab torches and set fire to police stations. He was like a

My theory is that King’s was a safe form of revolt. He mocked convention, but he didn’t exactly offer an alternative–nor did he suggest that people grab torches and set fire to police stations. He was like a

Regular visitor Texas A&M professor

Regular visitor Texas A&M professor

The Age of Reason was the first of a half-dozen or so books in a series published by Doubleday in the early 1960s. Edited by the veteran reporter John Gunther, author of the popular “Inside” books of the 1940s and 1950s, the series had the impressive title of “The Mainstream of the Modern World.” Although works of history, the books were all written by authors better known for fiction (Alec Waugh), reportage (Edmond Taylor), or miscellany (Nicolson), and all focused more on personalities than movements, politics, and larger issues.

The Age of Reason was the first of a half-dozen or so books in a series published by Doubleday in the early 1960s. Edited by the veteran reporter John Gunther, author of the popular “Inside” books of the 1940s and 1950s, the series had the impressive title of “The Mainstream of the Modern World.” Although works of history, the books were all written by authors better known for fiction (Alec Waugh), reportage (Edmond Taylor), or miscellany (Nicolson), and all focused more on personalities than movements, politics, and larger issues.

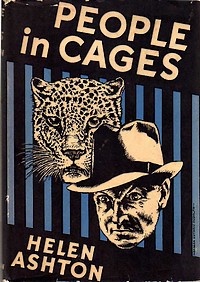

Brooks Peters added the following biographical information, along with a photo of Jane White, from the dust jacket of

Brooks Peters added the following biographical information, along with a photo of Jane White, from the dust jacket of  On the rare occasions when I’m back in the U.S., I always try to take time to stop by a public library and do some browsing through back issues of

On the rare occasions when I’m back in the U.S., I always try to take time to stop by a public library and do some browsing through back issues of  G. Wilson Knight subtitled this 1936 book “An Autobiographical Design,” and had he stuck to the autobiography and left the design out, I might have been less resentful about the several hours I devoted to assaulting its slopes. Perhaps I lack the mountaineering skills to attempt such a tower of intellect. But

G. Wilson Knight subtitled this 1936 book “An Autobiographical Design,” and had he stuck to the autobiography and left the design out, I might have been less resentful about the several hours I devoted to assaulting its slopes. Perhaps I lack the mountaineering skills to attempt such a tower of intellect. But