I learned of Thyra Samter Winslow from the two New Republic articles from 1934 on “Good Books That Almost Nobody Has Read”. In a letter responding to the articles, one O. Olsen of New York City wrote, “and there are Thyra Samter Winslow’s four books, The People Round the Corner, Picture Frames, Show Business and Blueberry Pie. All of these books are very good, and almost all of them have appeared on the 17-cent counters in the corner drug stores.”

I learned of Thyra Samter Winslow from the two New Republic articles from 1934 on “Good Books That Almost Nobody Has Read”. In a letter responding to the articles, one O. Olsen of New York City wrote, “and there are Thyra Samter Winslow’s four books, The People Round the Corner, Picture Frames, Show Business and Blueberry Pie. All of these books are very good, and almost all of them have appeared on the 17-cent counters in the corner drug stores.”

A quick Google of her name produced several interesting links: this biographical sketch from the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture and an article reprinted from the Southwest Times Record titled, “Thyra Samter Winslow: Woman Sets Fort Smith on Its Ear”. The encyclopedia piece notes that,

Published accounts of Winslow’s life are often contradictory. The authoritative work is a doctoral dissertation by Richard C. Winegard, who established Winslow’s biography from published records, Winslow’s own statements, and many interviews with informants in Fort Smith and elsewhere. He wrote, “She was restless, witty, independent, shrewd, kind, utterly mendacious, and sometimes completely dishonorable, and yet she is remembered most for her charm.”

The newspaper article offers equally contrasting views:

In New York Thyra Samter Winslow was part of the glamorous, sophisticated set other writers dubbed the “talk of the town.”

In Fort Smith, the “talk” she inspired often began with phrases like “that horrible woman.”

It also claims that one Fort Smith woman told Winegard, “indignantly,” “that he shouldn’t ‘write a dissertation about that horrible woman.'”

With recommendations like that, who wouldn’t want to know more?

From the opening words of “Little Emma,” the first story in Picture Frames, Winslow’s first collection of short stories, published by Knopf in 1923, I knew I liked this woman’s work:

When little Emma Hooper, from Black Plains, Iowa, came to Chicago to carve out her fortune, she did not leave behind her a sorrowing family who wondered about the fate of their dear child in the city. Neither did she sneak away from a cruel step-mother who had made life hard, unbearable. Emma’s family was quite glad to see her go.

Emma’s father was a member of the Knights of Pythias and worked in an overall factory. Her mother, a lazy, whiny woman, kept house, assisted unwillingly and incompetently by such daughters of the house as happened to be out of work. There were three of these daughters besides Emma and they all worked when jobs were not too difficult to get or keep. They spent their spare time trying to get married. There was one son. He was next in age to Emma, who was the second youngest. He smoked cheap cigars and hung around the livery stable and garage. His name was Ralph.

No room for nostalgia in this tough cookie’s heart. Little Emma, we learn, is a cute, conniving, ambitious young woman out to scramble as high up the social ladder as she could. She’s not pass romancing the town banker’s son purely for the financial benefit. After whispers start circulating when the lad and Emma are seen at the ice cream parlour, the father makes Emma a proposition: “If Miss Hooper would leave town, over the winter, say, a check for five hundred dollars would belong to her.” Emma takes the money and hightails to Chicago with no regrets. “She didn’t like Clarence much, anyhow. he was a silly, conceited thing, who told long tales about himself, and hadn’t changed much, in fact, since his sniffy boyhood days.”

In “Corinna and Her Man,” the last story in Picture Frames, Winslow shares the thoughts of one of her sharp young women: “In spite of her mother, she realized that men weren’t superior people, after all. They were rather more stupid than women, on the whole, a bit heavy, with a thick sense of humor. Men were ashamed to show emotions, easy victims of flattery.” This outlook allows characters such as Mamie Carpenter, the subject of another Winslow story, to work her way from the wrong side town into a mansion on Maple Road solely by manipulating the emotions of Marlin Embury, heir to one of the town’s few fortunes.

Winslow’s characters live in a world of “sets.” The desirable set, of course, is the “society set,” because all others are considered outcast, uninteresting, or shameful. One suspects the fact that Winslow’s family was Jewish and her father a shopkeeper put her at a permanent disadvantage in Fort Smith’s hierarchy of sets. Not that places like Fort Smith or Millersville, Mamie Carpenter’s town, had been around long enough to claim any real roots to their sets:

Mamie scorned Millersville’s social pretentions. She knew that in some cities, London and New York, maybe, there was society, real people with generations of good blood back of them, and money and breeding. People like that Mamie could look up to. But she knew Millersville. In Millersville, what did society amount to? A joke, that’s what it was. No one really came to anything, did anything.

The Elwood Simpsons, the leaders of Millersville society–look at them! There was a little grave in Oakdale Cemetery that Mamie knew all about–and it was closely connected with the girlhood of Mrs. Elwood Simpson–and there were other babies who did not die but who arrived at equally inopportune times. The Coakleys were one of Millersville’s oldest and best families–and Frank Coakley’s half-brother spend most of his time in jail, and his other half-brother, Bill, was half-witted, went around with his tongue hanging out and saying silly things. The Binghams–ugh–they had to get their servants out of town, and sometimes at the last minute had to break engagements because some one in their third floor would cry and scream–their oldest daughter, some said it was.

Passages like think make Picture Frames seem a bit like Winesburg, Ohio writ by Dorothy Parker: it’s a hard world, but one where cynicism goes a long way as insulation against the bitterest blows. Winslow’s sensibility also shares much with that of Balzac: the selfish always end up on top, the soft-hearted get used and forgotten, and everyone is keeping score.

Not that escape from small towns is any panacea. A number of the stories in Picture Frames focus on the realities of city life.

In “A Cycle of Manhattan,” the longest and weakest story in the collection, Winslow takes a family of Lithuanian Jews, the Rosenheimers, from the day they step off the boat onto Ellis Island to a time, some thirty years later, when “Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln Ross, well-dressed, commanding, in their fifties” come to visit the Greenwich Village studio of their son, Manning Cuyler Ross (nee Emmanuel Rosenheimer). Step by step, the family moves up the economic and social ladder. With each step, something of their roots is shed. Rosenheimer becomes Rosenheim, which in turns becomes Rosen and, finally, the ethnically-blank Ross. The father shaves his beard and forelocks, the mother abandons her shawl. By the time the story ends, the family has left so much of their original selves behind that only the father recognizes Manning’s studio as the same tenement apartment in which they started their life in Manhattan. “This is the way to live! None of your middle-class fripperies. Plain living–this is the life!” proclaims Manning.

In “City Folks,” in fact, the story pivots around the choice facing Joe and Mattie, a couple living in a small apartment in Manhattan. Joe’s father is ailing and wants them to return to Burton Center and take over the family store. “Burton Center will look awfully good–folks take an interest in you, there,” Joe muses. But in the course of the day, they both get caught up in–well, not much more than the mere pace of city life. Despite the fact that they stare out of their window “across to the factory-like, monotonous row of apartment houses opposite, where innumerable lights twinkled from other little caves, where other little families lived humdrum, unmarked, inconsequential, grey,” they place more importance on such coincidences as seeing James Montgomery Flagg at a Liberty Bond rally or Billie Burke getting out of a limousine. “We’re city folks!” they conclude.

Picture Frames received an enthusiastic critical welcome when it was published. Edna Ferber, one of the most successful novelists of the time, led the applause: “These short stories are character studies, penetrating, keen, pitiless. No one in this country is doing this sort of thing as well as Thyra Winslow.” She did, however, regret Winslow’s lean style, referring to it as, “Hard, tough, common, little Anglo-Saxon words about hard, tough, common little American people.” Burton Rascoe, reviewing for the New York Tribune, called the stories “hard, metallic”–but also described Winslow’s work as “distinctly original, the method of presentation new, the point of view fresh, challenging and distinctive.”

Winslow published four other story collections–The People Round the Corner (1927), Blueberry Pie (1932), My Own, My Native Land (1935), and The Sex Without Sentiment (1957). She also published one novel, Show Business (later republished as Chorus Girl) in 1926.

Although not one of the legendary Algonquin Round Table set, Winslow was an active and well-known member of the New York literary scene through the 1920s and 1930s. Several of her stories were made into movies and she worked at times as a writer for studios. As the rage for magazine fiction began to fade in the 1940s, she was forced to take jobs writing diet books and place stories with less mainstream magazines such as Amazing Science Fiction. Although she returned to Fort Smith on occasion, townspeople were unwilling to allow her picture to hung in the town library.

I look forward to reading more of her “hard, metallic” stories. After all, one could use these words to describe most fine jewelry.

Locate a Copy

- Find it at Amazon.com: Picture Frames

if they ever list a copy

- Find it at Amazon.co.uk: Picture Frames

- Find it at AddAll.com: Picture Frames

Born in California in 1895, Storm studied engineering at Stanford and went into the nascent field of radio engineering. His first novel,

Born in California in 1895, Storm studied engineering at Stanford and went into the nascent field of radio engineering. His first novel,

Storm’s work in radio, along with years of dealing with the maritime business, shows in many telling details that anchor his story in a credible reality. But there is also a sense of Storm as puppeteer, manipulating his players, pushing them into extremis just to see the violence of their recoil. I found myself thinking of Herbert Clyde Lewis’

Storm’s work in radio, along with years of dealing with the maritime business, shows in many telling details that anchor his story in a credible reality. But there is also a sense of Storm as puppeteer, manipulating his players, pushing them into extremis just to see the violence of their recoil. I found myself thinking of Herbert Clyde Lewis’  Ben Daniel Piazza, we learn from his

Ben Daniel Piazza, we learn from his  You’ve probably seen Ben Piazza. His

You’ve probably seen Ben Piazza. His

In early 1934, Malcolm Cowley, then literary editor of

In early 1934, Malcolm Cowley, then literary editor of

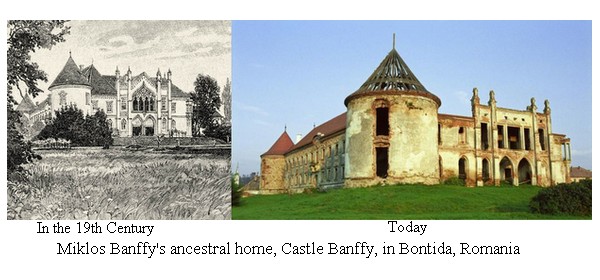

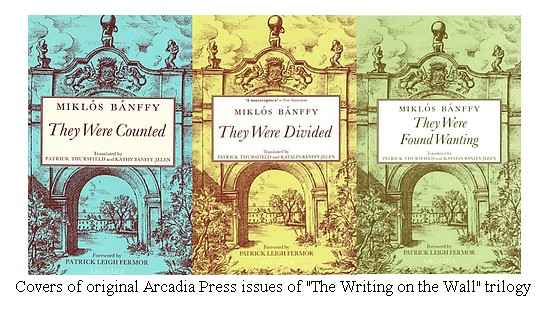

Banffy, or, to use his full title,

Banffy, or, to use his full title,

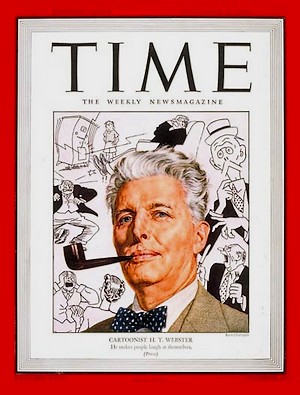

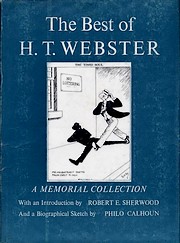

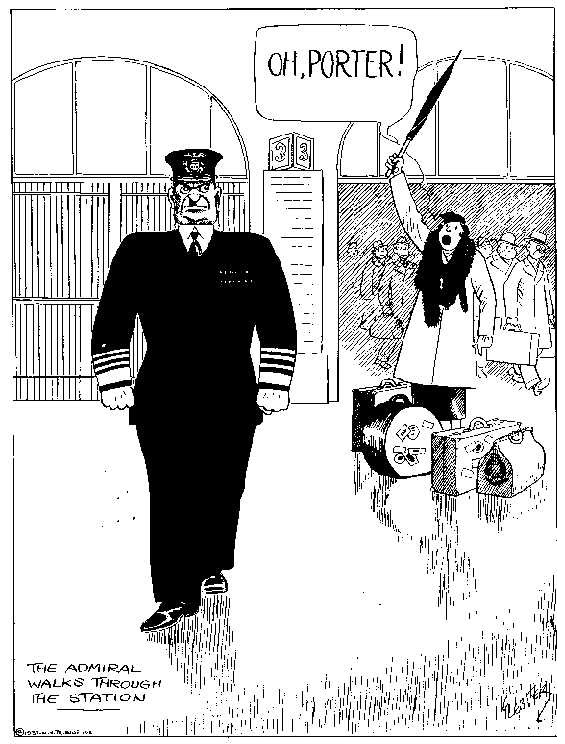

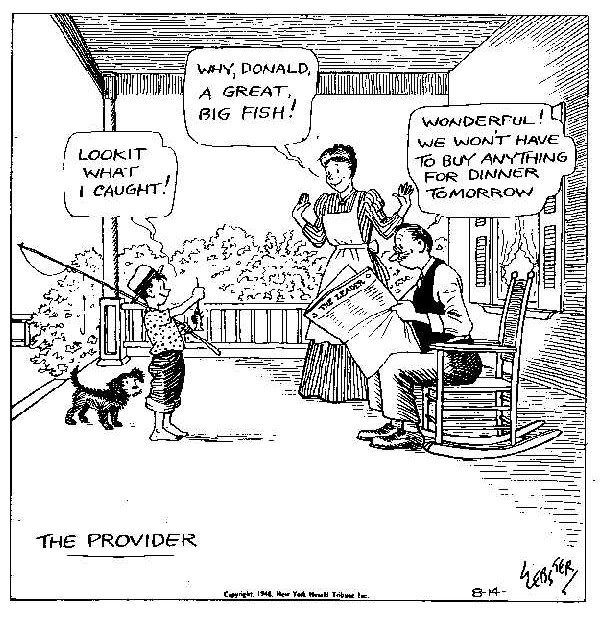

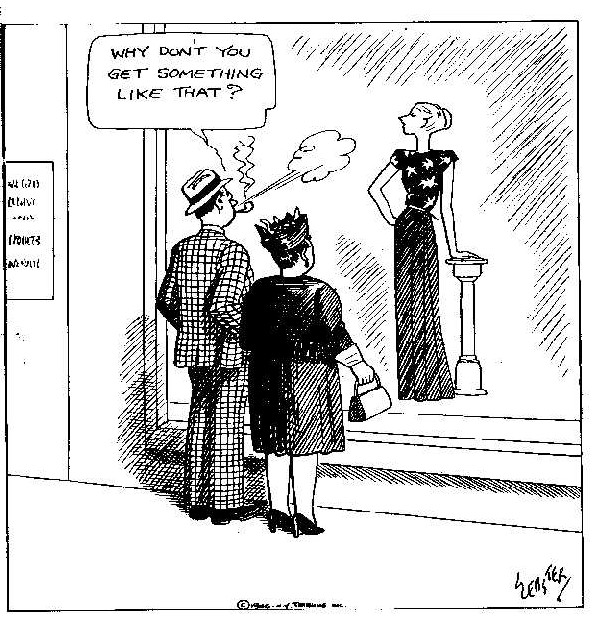

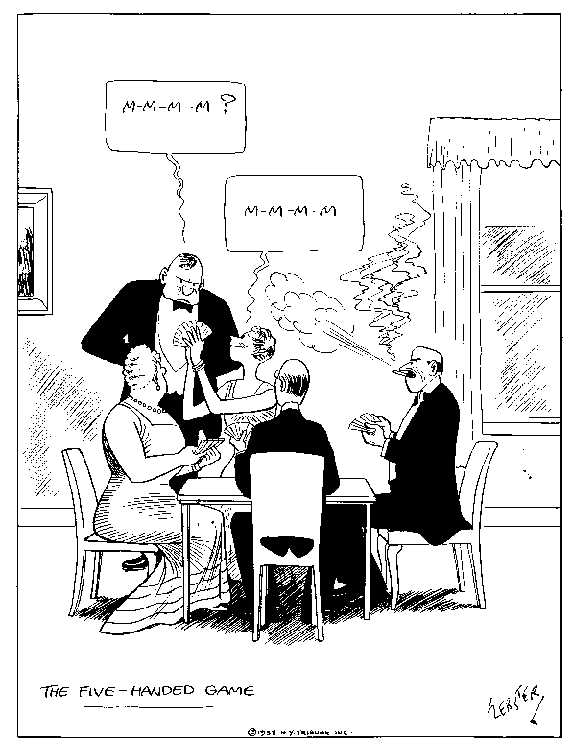

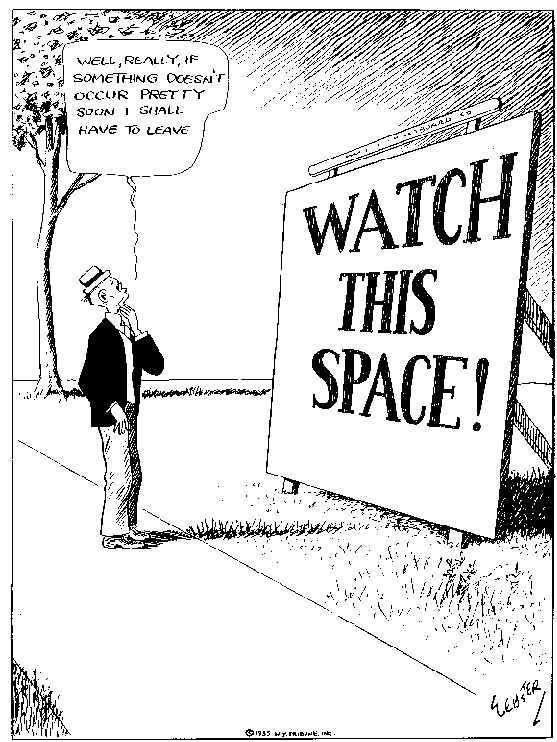

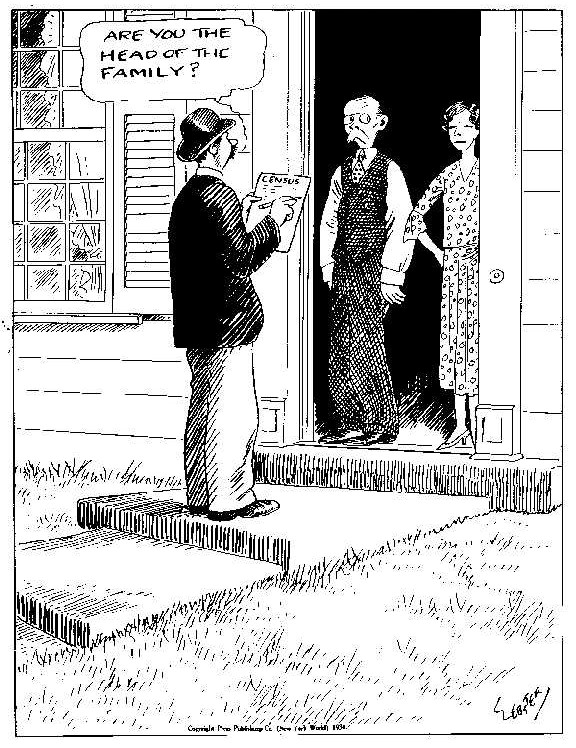

Webster published over 15,000 panels over the course of 40-plus years as a newspaper cartoonist. A memorial collection of his cartoons,

Webster published over 15,000 panels over the course of 40-plus years as a newspaper cartoonist. A memorial collection of his cartoons,

dreamed about Bokhara, a fabulous city that was then more difficult to access than Tibet. I opened my eyes upon the end of not only the nineteenth century but of a second Puritan age. An epoch passed away while I was learning to speak and walk. Its influence remains as the start of memory and as a measuring rod for progress that even Edwardian survivors lack.

dreamed about Bokhara, a fabulous city that was then more difficult to access than Tibet. I opened my eyes upon the end of not only the nineteenth century but of a second Puritan age. An epoch passed away while I was learning to speak and walk. Its influence remains as the start of memory and as a measuring rod for progress that even Edwardian survivors lack. I couldn’t resist starting in with the most ridiculous title in the bunch:

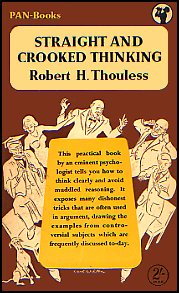

I couldn’t resist starting in with the most ridiculous title in the bunch:  Donald Schon’s

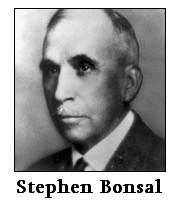

Donald Schon’s  Being selected for the Pulitzer Prize is no guarantee of that anyone will remember your work–at least not more than ten years afterward. Take

Being selected for the Pulitzer Prize is no guarantee of that anyone will remember your work–at least not more than ten years afterward. Take  Bonsal’s book opens on the eve of the Armistice and ends a little over a year later, with the Senate’s rejection of the Treaty. He worked alongside House, and later Wilson, through the preparations and initial sessions of the Conference. A veteran foreign correspondent fluent in a number of European tongues, he acted as an emissary to many of the other delegations and as a personal advisor to House and Wilson. He remained at the negotiating tables throughout most of the Conference, taking only a break of a few weeks to accompany South African General Jan Christian Smuts on a mission to Austria, Hungary, and Serbia in March and April 1919.

Bonsal’s book opens on the eve of the Armistice and ends a little over a year later, with the Senate’s rejection of the Treaty. He worked alongside House, and later Wilson, through the preparations and initial sessions of the Conference. A veteran foreign correspondent fluent in a number of European tongues, he acted as an emissary to many of the other delegations and as a personal advisor to House and Wilson. He remained at the negotiating tables throughout most of the Conference, taking only a break of a few weeks to accompany South African General Jan Christian Smuts on a mission to Austria, Hungary, and Serbia in March and April 1919. I think it was in the long-gone Filippi’s Books in Seattle that I came across the

I think it was in the long-gone Filippi’s Books in Seattle that I came across the  Simon and Schuster published at least seven other Fireside books on sports and games, including:

Simon and Schuster published at least seven other Fireside books on sports and games, including:

These were not at all like my mom’s cookbooks. These were cookbooks written for men by a guy without a shred of doubt about his studliness. What cookbook written by a woman would put “Meat” at the front, on the very first page? And lead off with, “How to Make Real Corned Venison, Antelope, Moose, Bear and Beef”? The last is just a concession to the little ladies, I’m sure. The author,

These were not at all like my mom’s cookbooks. These were cookbooks written for men by a guy without a shred of doubt about his studliness. What cookbook written by a woman would put “Meat” at the front, on the very first page? And lead off with, “How to Make Real Corned Venison, Antelope, Moose, Bear and Beef”? The last is just a concession to the little ladies, I’m sure. The author,

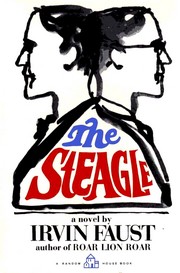

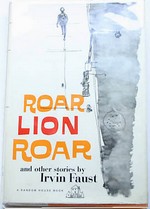

“Opening this book is like clicking on a switch: at once we hear the electric hum of talent,” Stanley Kauffmann wrote in his New Republic review of Irvin Faust’s first book of fiction,

“Opening this book is like clicking on a switch: at once we hear the electric hum of talent,” Stanley Kauffmann wrote in his New Republic review of Irvin Faust’s first book of fiction,  As he told Don Swaim in a 1985 interview (available on the

As he told Don Swaim in a 1985 interview (available on the  In the title story of

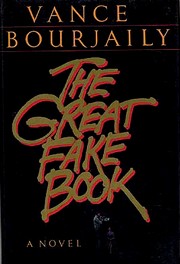

In the title story of  It pains me to start 2010 with two pans in a row, but few books have disappointed me as much as Vance Bourjaily’s little-known 1986 novel,

It pains me to start 2010 with two pans in a row, but few books have disappointed me as much as Vance Bourjaily’s little-known 1986 novel,