A mad stone is a stone-like mass–a hairball, really–taken from the stomach of a deer and reputed to have a magical power of curing rabies and snake bites. Although an actual mad stone plays a minor role in Lorna Beers’ novel, the Minnesota (or Dakota–Beers does not identify specific locations) countryside serves as the symbolic cure for the “poisoned” souls of her protagonists.

A mad stone is a stone-like mass–a hairball, really–taken from the stomach of a deer and reputed to have a magical power of curing rabies and snake bites. Although an actual mad stone plays a minor role in Lorna Beers’ novel, the Minnesota (or Dakota–Beers does not identify specific locations) countryside serves as the symbolic cure for the “poisoned” souls of her protagonists.

Louis and Ollie are a mismatched pair. Louis is a penniless would-be visionary whose utter failure to provide for his family in the great metropolis (Chicago? Minneapolis?) has finally led Mattie, his wife, to drag him and their three children back to her father’s farm. Ollie is the wife of Vandiver Hackett, a tycoon of some sort, sent off to Hackett’s family home as punishment for a real or imagined adultery. They meet on the train out to the country and quickly recognize the one thing they share in common: an inability to go with the flow of prevailing values and habits.

At some point in the past, Louis was an aspiring preacher, a young man whose fervent sermons drew crowds from all over the area. But he was also fascinated with mathematics, science, and the movement toward a historical view of Jesus popularized by Ernest Renan. He heads off to the city to pursue a self-crafted course of studies, and spends hours scribbling away in endless notebooks while Mattie struggles to feed and clothe their children. When homelessness looms, she forces Louis to return to the country, where at least she has some assurance that their hungry mouths will be fed.

Beers subjects us to many passages of Louis’ passionate monologues about science, religion, and the follies of man, but a small sample should suffice to demonstrate what a windblown pedant he is:

Oh, wandering Jew, doomed to change your essence from age to age, to mirror the vanity of the current custom. Now knight-errant, now Eastern king, now Greek athlete with delectable flesh that felt no pain lifted sensuously from the cross: now a showman exposing the stigmata on your hands and feet … drop your coins into the wicker tray, brethren! Now you have been taken arm-in-arm with scholarship, and you walk about the philosophical peripatetic paths saying “I am the word!”

Louis is hell-bound not to go gentle into his good night. “Never will I bow my spirit to the originator and the torturer of our sentience. Never will I sit and purr on the lap of God!” he exclaims at one point.

Ollie, on the other hand, is sophisticate–well-dressed, well-read, well-traveled, and utterly bored with everything. She enjoys taunting Molly, the Hackett’s cook, about the contradictions of her Catholic faith:

“‘Molly, why aren’t you eating the mince pie?’ ‘Mrs. Vand,’ I told her, ‘this day is sacred with us. I don’t eat flesh of any kind,’ I told her. ‘Flesh?’ she said. ‘Suet, Miss. There is suet in mince pie.’ “Oh, suet,’ she said thoughtfully. ‘What is suet, Molly?’ ‘Fat of beef,’ I tell her, since she knew so little. ‘Oh, it’s fat of beef, is it?’ she said. ‘Your God doesn’t like fat of cows?’ And she reached down and nipped off a bit of the crust of my custard pie and looked at it very sharply, turning it this way and that. ‘Molly,’ she said ‘will you ask something of your Prayste for me? Why your Lord likes fat of pigs and doesn’t like fat of cows. Lard and suet, well, well,’ she said, ‘I had never imagined to find Him so particular.’ Before I could say a word she had her impudent face out of the door.”

Soon after their arrival, Beers manages to bring the two together on long nighttime walks and other escapes from the confines of small town and farm routines. Most of their time together consists of impassioned monologues by Louis and sly cross-examinations by Ollie. Neither manages to notice the richness of life and nature that surrounds them, and Beers’ many lyrical descriptions of the countryside draw stark counterpoint to her protagonists’ arid intellectuality. Ollie literally hates nature: “It was malignant. Malignant. It was only in the marts of men that she felt safe, where their chatter, their irrational habits made her feel secure in her own intelligence.”

Beers also contrasts the two mind-bound lovers (and I use this word very loosely, as there is never a suggestion that there is anything physical in their relationship) with the two other principal characters in the novel, Vand Hackett’s sister Nanda and Louis’ wife Mattie. While Louis and Ollie are off on their fools’ errands, Nanda and Mattie are, at the same time, bound in by conventions and in close touch with Mother Earth:

Mattie leaned over, watching the ants rebuild their houses under the upraised heel of God. And she became aware of a stalk of wild teasel standing in the sod just outside the cultivated soil. She looked at it as she might study the features of one rendered unique by being the object of her sudden falling in love. She looked at its base as it rose above the wild grass. The stalk was thick and ribbed, its irregular hollow circumference grown over with green hairs and spines, a natural armor against sudden closing fingers. Pairs of spear-like leaves were set at intervals up the stem, and like the oval knob of a sceptre, there was borne upon each stalk an oblong head. Several of these cones were green and immature, but upon tow of them were set clusters about the middle of pale lavender flowers.

She sat looking at the weed, wondering about the nature of its existence, of how the sap flowed through its stems, of how it flowered and shook its leaves in isolated being, subject to momentary uprooting by the sharp blade of her hoe.

As The Mad Stone goes on, Louis and Ollie grow more reckless, doing little to hide their meetings. Chaste though they may remain, theirs was a time when just the appearance of impropriety was enough to earn a community’s disapproval. It seems clear that, in one way or another, they are headed on a path to self-destruction.

Yet just before everything spins out of control, Louis pulls himself up by the bootstraps and decides to head back to the city–this time committed to becoming a science teacher and earning an honest living. Ollie also returns to town, kept from crashing by the more obvious restraint of a telegram from her husband calling her back. Mattie stays to help her father and watch her children continue to grow ever more rosy-cheeked on the fresh air and fresh produce of the farm.

This late turn-around in the narrative seems as miraculous and implausible as the mad stone’s cure of rabies. It’s clear that Beers was, at heart, uncomfortable with a world where people crash and burn. Her loyalty lay with the regenerative powers of nature, not the self-destructive powers of man.

The Mad Stone was Lorna Beers’ third novel, following Prairie Fires (1925) and A Humble Lear (1929). It won the Avery Hopwood award for fiction from the University of Michigan and was generally well-received among critics. It was, however, her last published adult novel.

According to her Wikipedia biography, Beers’ career was derailed by the need to care for her husband’s crippling emotional problems. She wrote and published several books for younger readers and, decades later (1966), Wild Apples and North Wind, a memoir of life on a Vermont farm.

Wild Apples is said to have been one of Annie Dillard’s inspirations, and the gorgeous writing about nature one finds throughout The Mad Stone is by far the best part of the book. One sticks with the novel not for the tiresome tragedy of Louis and Ollie but for the lovely epiphanies of Mattie and Nanda as they drink in the energy, beauty, and complexity of the wild and cultivated life all around them.

Find a copy

- Amazon.com: The Mad Stone

- Amazon.co.uk: The Mad Stone

- AddAll.com: The Mad Stone

- Find it in WorldCat: The Mad Stone

I learned of Thyra Samter Winslow from the two New Republic articles from 1934 on

I learned of Thyra Samter Winslow from the two New Republic articles from 1934 on

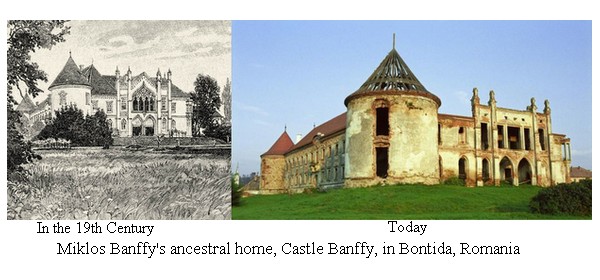

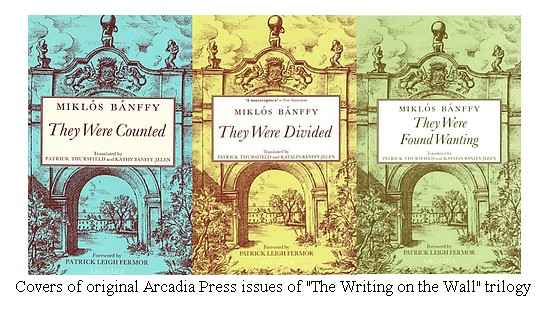

Banffy, or, to use his full title,

Banffy, or, to use his full title,

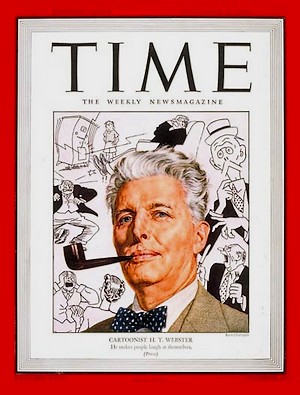

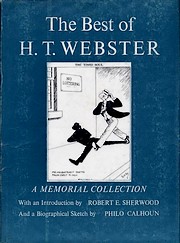

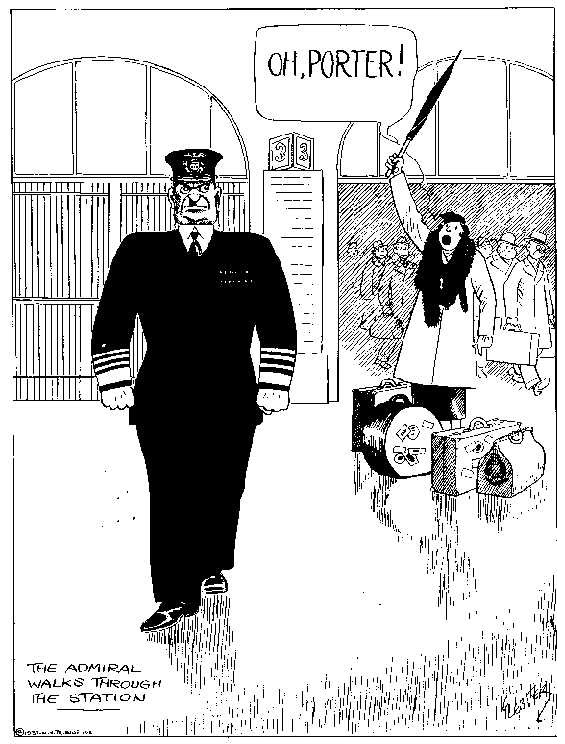

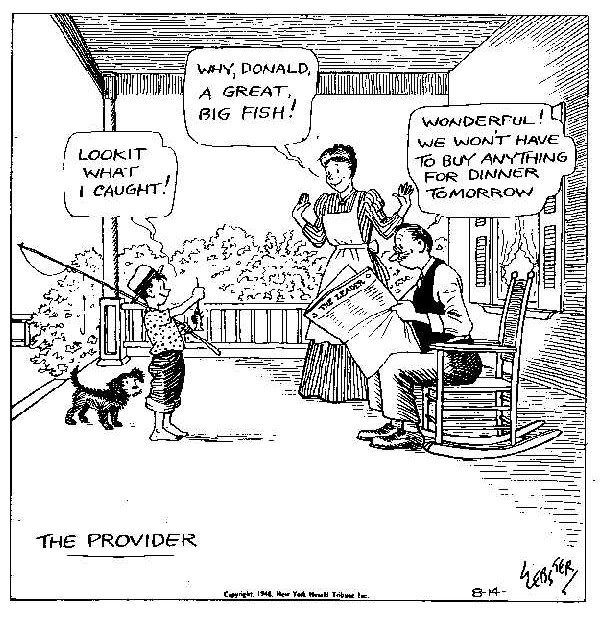

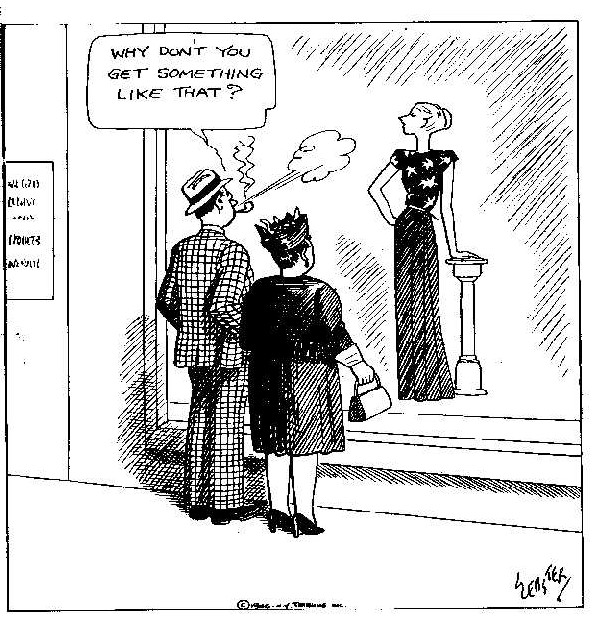

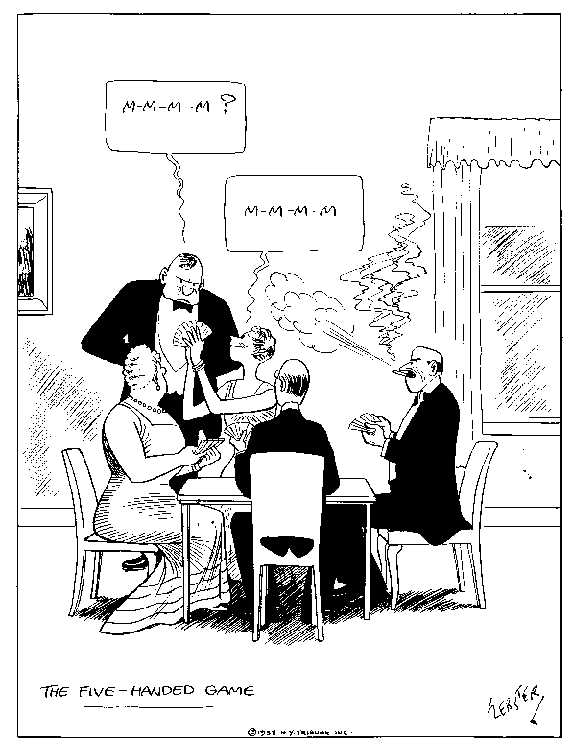

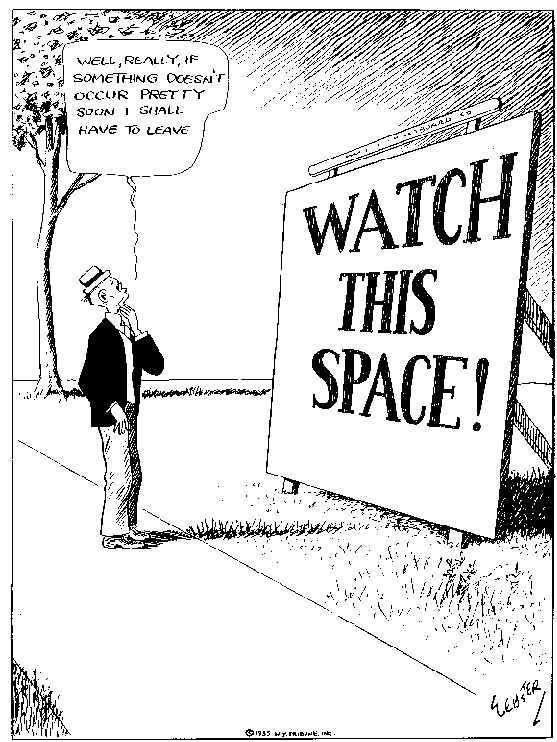

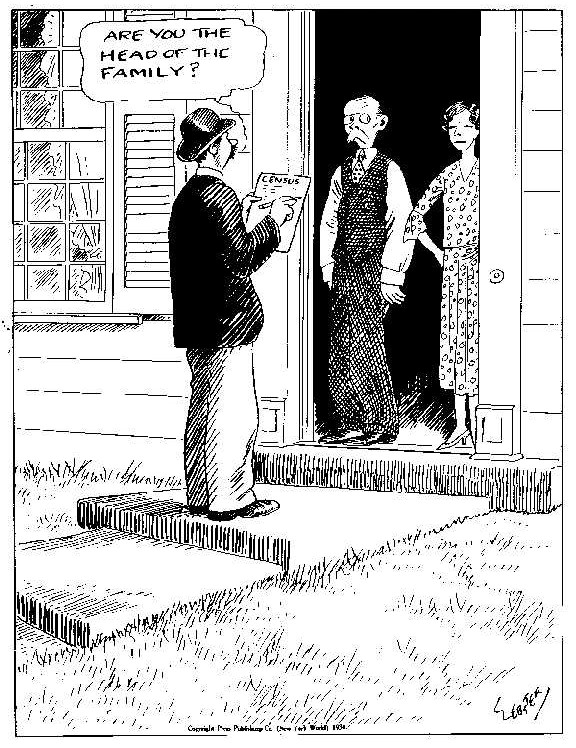

Webster published over 15,000 panels over the course of 40-plus years as a newspaper cartoonist. A memorial collection of his cartoons,

Webster published over 15,000 panels over the course of 40-plus years as a newspaper cartoonist. A memorial collection of his cartoons,

I couldn’t resist starting in with the most ridiculous title in the bunch:

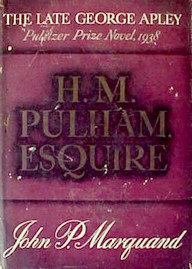

I couldn’t resist starting in with the most ridiculous title in the bunch:  Being selected for the Pulitzer Prize is no guarantee of that anyone will remember your work–at least not more than ten years afterward. Take

Being selected for the Pulitzer Prize is no guarantee of that anyone will remember your work–at least not more than ten years afterward. Take  Bonsal’s book opens on the eve of the Armistice and ends a little over a year later, with the Senate’s rejection of the Treaty. He worked alongside House, and later Wilson, through the preparations and initial sessions of the Conference. A veteran foreign correspondent fluent in a number of European tongues, he acted as an emissary to many of the other delegations and as a personal advisor to House and Wilson. He remained at the negotiating tables throughout most of the Conference, taking only a break of a few weeks to accompany South African General Jan Christian Smuts on a mission to Austria, Hungary, and Serbia in March and April 1919.

Bonsal’s book opens on the eve of the Armistice and ends a little over a year later, with the Senate’s rejection of the Treaty. He worked alongside House, and later Wilson, through the preparations and initial sessions of the Conference. A veteran foreign correspondent fluent in a number of European tongues, he acted as an emissary to many of the other delegations and as a personal advisor to House and Wilson. He remained at the negotiating tables throughout most of the Conference, taking only a break of a few weeks to accompany South African General Jan Christian Smuts on a mission to Austria, Hungary, and Serbia in March and April 1919. I think it was in the long-gone Filippi’s Books in Seattle that I came across the

I think it was in the long-gone Filippi’s Books in Seattle that I came across the  Simon and Schuster published at least seven other Fireside books on sports and games, including:

Simon and Schuster published at least seven other Fireside books on sports and games, including:

These were not at all like my mom’s cookbooks. These were cookbooks written for men by a guy without a shred of doubt about his studliness. What cookbook written by a woman would put “Meat” at the front, on the very first page? And lead off with, “How to Make Real Corned Venison, Antelope, Moose, Bear and Beef”? The last is just a concession to the little ladies, I’m sure. The author,

These were not at all like my mom’s cookbooks. These were cookbooks written for men by a guy without a shred of doubt about his studliness. What cookbook written by a woman would put “Meat” at the front, on the very first page? And lead off with, “How to Make Real Corned Venison, Antelope, Moose, Bear and Beef”? The last is just a concession to the little ladies, I’m sure. The author,

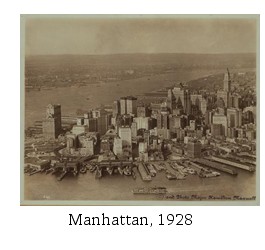

The story takes us through the day in the minds of the residents of a rooming house in the Greenwich Village – Lower Fifth Avenue area of Manhattan. Mr. Kittredge–we never learn his first name–is a depressed, dyspeptic, world-weary World War One veteran who plans to commit suicide that night. Betty Carson is a young girl from Cape Cod, now working at Macy’s. Betty has discovered that she’s pregnant, by a man named Joe Henderson who left a month ago and hasn’t contacted her since. Having given up hope of seeing him again, Betty has decided to visit an abortionist after work.

The story takes us through the day in the minds of the residents of a rooming house in the Greenwich Village – Lower Fifth Avenue area of Manhattan. Mr. Kittredge–we never learn his first name–is a depressed, dyspeptic, world-weary World War One veteran who plans to commit suicide that night. Betty Carson is a young girl from Cape Cod, now working at Macy’s. Betty has discovered that she’s pregnant, by a man named Joe Henderson who left a month ago and hasn’t contacted her since. Having given up hope of seeing him again, Betty has decided to visit an abortionist after work.

As the Russians approach, Stefan and Hannes are moved, along with other inmates, towards the West. They manage to escape when an Allied plane attacks their train, causing it to derail, but Hannes is wounded and soon dies. Stefan is interned again, this time by the Americans, as a displaced person. An American G.I., a Southerner named Moon (more symbolism), takes a liking to Stefan and eventually adopts him. After a brief spell in South Carolina, full of atmosphere straight out of Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor, Stefan returns to Europe.

As the Russians approach, Stefan and Hannes are moved, along with other inmates, towards the West. They manage to escape when an Allied plane attacks their train, causing it to derail, but Hannes is wounded and soon dies. Stefan is interned again, this time by the Americans, as a displaced person. An American G.I., a Southerner named Moon (more symbolism), takes a liking to Stefan and eventually adopts him. After a brief spell in South Carolina, full of atmosphere straight out of Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor, Stefan returns to Europe.  Significant, though? Sadly,

Significant, though? Sadly,

Of course, the Germans didn’t attack the French and British in April 1940, but two months later, in June, and when they did, they wisely bypassed the Maginot Line in favor of a blitzkrieg through the Ardennes and the Lowlands. This is a major reason why

Of course, the Germans didn’t attack the French and British in April 1940, but two months later, in June, and when they did, they wisely bypassed the Maginot Line in favor of a blitzkrieg through the Ardennes and the Lowlands. This is a major reason why  Reading Isa Glenn’s novel,

Reading Isa Glenn’s novel,  Glenn published a total of eight novels in the space of nine years. Two–

Glenn published a total of eight novels in the space of nine years. Two– It’s a real shame, for

It’s a real shame, for

Not there isn’t any action in

Not there isn’t any action in  It’s particularly noteworthy when one realizes who

It’s particularly noteworthy when one realizes who

The writing is what makes

The writing is what makes  Paterson’s three novels published between 1933 and 1940–

Paterson’s three novels published between 1933 and 1940– Compared to Ford, however, Marquand is more craftsman than artist. His prose style is never much more than workmanlike, and he has at time a tendency to fill pages more for the sake of providing his audience with a good thick read than for shaping his story. But observation, not artistry, is Marquand’s long suit. He is an ideal observer–a novelist of society, perhaps America’s best after Edith Wharton. Like Wharton, he is both immersed in society, having been raised in family highly sensitive to–if not highly placed in–Boston society, and able to detach himself and note its many ironies and shortcomings. And

Compared to Ford, however, Marquand is more craftsman than artist. His prose style is never much more than workmanlike, and he has at time a tendency to fill pages more for the sake of providing his audience with a good thick read than for shaping his story. But observation, not artistry, is Marquand’s long suit. He is an ideal observer–a novelist of society, perhaps America’s best after Edith Wharton. Like Wharton, he is both immersed in society, having been raised in family highly sensitive to–if not highly placed in–Boston society, and able to detach himself and note its many ironies and shortcomings. And

Appel’s career as a writer spanned five decades and his work ranged from serious fiction such as

Appel’s career as a writer spanned five decades and his work ranged from serious fiction such as