“Any man that wants a job can get it!”

I believe that this statement, despite the deep groove that it has worn in the average unthinking mind, is utterly without foundation in fact. I want to tell you why I believe that it is not true. I want to tell you how I tramped for nine weeks through the streets of a great American city, and how I was unable upon application to secure work at a wage that would keep me alive.

Thus opens A Honeymoon Experiment, a remarkable little book published in 1916 by a remarkable couple, Margaret and Stuart Chase.

When considering how to spend their honeymoon after marrying in the summer of 1914, the Chases decided to take it as an opportunity to engage in an unusual life experiment. From the start, they had been attracted to each other by a passion for independent thinking. At the age of 23, Stuart Chase had composed as his personal credo, “I must choose my own path… from among the many and follow it in all faith and trust until experience bids me seek another,” and he stuck to it with exceptional success throughout the rest of his life. His wife, Margaret Hatfield Chase, a teacher at a number of alternative schools, shared his willingness to venture outside conventional patterns.

And so, Chase wrote,

We decided to devote our honeymoon to the task of finding out more concerning the matters that so profoundly perplexed us. Ever since our first talks together we had wanted to know how it felt to live beyond the pale of family and class influence. Here was our chance. We could utilize these honeymoon weeks to start clean and clear at the bottom.

What they decided to do–after a few weeks canoeing in the Ontario woods–was to go to Rochester, New York “… as a homeless, jobless, friendless couple, and see what it meant to face existence without an engraved passport.” It was, for 1914, a unique choice, and even in the century since, only a rare few newlyweds have taken such a leap into the unknown.

A Honeymoon Experiment is told in two part: “The Groom’s Story” and “The Bride’s Story.” They picked Rochester based on its size, its industrial base (Eastman Kodak, a shirt collar factory, other light manufacturing), and the fact that they knew no one there. They donned their oldest clothes, boarded a train, and got off in Rochester as “Mr. and Mrs. Chase,” a bookkeeper and his wife trying to make a go after losing jobs in Boston.

Their hypothesis was simple: with perserverance, they would be able to land jobs earning a decent wage and survive on solely on what they made. They gave themselves nine weeks.

They failed.

Each morning they made plans of businesses to inquire at, employment ads to answer, agencies to visit, fending as best they could in an age when there were no state services to help out the jobless. They walked miles around the city as tram fare became a luxury. Food and shelter became their “supreme masters.” As days went on without success, they grew more exhausted and depressed. They conceded their battle against the dust, dirt, and grime pervasive in their quarters: “One’s standards collapse.” And they understood just how precarious life was on 1914’s poverty line.

Stuart applied for 92 jobs in nine weeks, not to count the number of “opportunities”–i.e., scams, such as selling useless cures and shoddy gadgets door-to-door–he investigated. In the end, he landed one–a part-time job as a bookkeeper, and that only through another tenant.

Margaret fared only slightly better. She also applied for 92 positions. She did get hired at several businesses, only to discover just how dangerous and intolerable working conditions, particularly for women, were in the days before occupational safety standards. And she also learned that male employers had no compunctions about intimidating and harassing their female employees. She usually had to leave within two to three days.

The problem of survival was multiplied by the fact that most of what few jobs were available were at wages below the level at which they could cover their rent and food. Stuart and Margaret calculated that, at twenty five dollars a week, a couple could manage to maintain a tolerable quality of life, though one without any type of savings, insurance, or other security. In their best week, they together made fifteen.

“So long as there is steadiness of employment, there is at least some continuity and some hope in existence,” Stuart wrote. They learned for themselves, as well as from other tenants, how quickly the fall into hunger, degradation, sickness, homelessness, and the break-up of families could happen when a living income is lost.

At one point, Stuart–hungry, tired, and frustrated after “when an army of cockroaches invaded” their room–tells Margaret to get her hat so they can head off to a respectable hotel for the night. “You quitter!” Margaret chides him.

When they finally end the experiment and get ready to return to their normal lives, Margaret has a moment’s second thought:

“Let’s stay here and be free and unconventional and and human for ever and ever!”

“In this room,” I asked, “for ever and ever? Could you stick it out?”

“No,” said Margaret soberly; “I don’t suppose I could stick it out in this room for ever and ever.”

Our eyes wandered over the battered furniture, the peeling plaster, the stained ceiling, the unwashed tin dishes.

“How long could we stick it out?” I mused.

They agreed that they would write this book to try to demonstrate to other Americans the consequence of having no legal guarantees of employment and a living wage.

As I read A Honeymoon Experiment, I kept thinking that it would be an excellent text for high schoolers to read. Largely contemporaneous with Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, which is commonly assigned in English and American history classes, it may lack the same level of melodrama and “gross out” factors, but it’s also very straightforward, told mostly from a very accessible personal standpoint–and not weighted down with Sinclair’s club-footed prose. It’s an effective way to convey what the economic, social, and political conditions were in the U. S. a hundred years ago–or, to steal the title from a book edited by Otto Bettmann: The Good Old Days–They Were Terrible!.

Margaret and Stuart Chase divorced in 1922. Stuart had become by then a crusading staffer on the Federal Trade Commission, attacking industry corruption and practices. When the meatpacking industry strong-armed President Harding into getting rid of Stuart (he was called a “Red accountant” in Congress), Stuart fell back on his personal credo and seized it as an opportunity and chose his own path.

Margaret and Stuart Chase divorced in 1922. Stuart had become by then a crusading staffer on the Federal Trade Commission, attacking industry corruption and practices. When the meatpacking industry strong-armed President Harding into getting rid of Stuart (he was called a “Red accountant” in Congress), Stuart fell back on his personal credo and seized it as an opportunity and chose his own path.

He collaborated with the economist Thorstein Veblen to attack corporate inefficiencies and unfair trade practices. He became a prolific writer on a wide variety of topics and vocal advocate for reforms. His 1934 book with F. J. Schlink, Your Money’s Worth, was one of the first to address the cause of consumer rights. The Tyranny of Words

, one of the earliest popular works on semantics, is still in print today. In Roads to Agreement

he dealt with negotiation techniques, psychology, and human relations, and in Guides to Straight Thinking

he showed how logic can be used to deal with everyday problems.

In the 1950s he wrote and spoke in favor of disarmament; in 1968, at the age of eighty, he was calling for measures to reduce pollution in Rich Land, Poor Land. He died at the age of 97 in 1985 with 35 books to his name.

A Honeymoon Experiment is available from several direct-to-print publishers via Amazon.com, but you can get it for free in ASCII, EPUB, PDF, Kindle, and other digital formats from the Internet Archive.

dreamed about Bokhara, a fabulous city that was then more difficult to access than Tibet. I opened my eyes upon the end of not only the nineteenth century but of a second Puritan age. An epoch passed away while I was learning to speak and walk. Its influence remains as the start of memory and as a measuring rod for progress that even Edwardian survivors lack.

dreamed about Bokhara, a fabulous city that was then more difficult to access than Tibet. I opened my eyes upon the end of not only the nineteenth century but of a second Puritan age. An epoch passed away while I was learning to speak and walk. Its influence remains as the start of memory and as a measuring rod for progress that even Edwardian survivors lack. Being selected for the Pulitzer Prize is no guarantee of that anyone will remember your work–at least not more than ten years afterward. Take

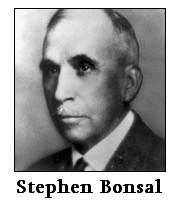

Being selected for the Pulitzer Prize is no guarantee of that anyone will remember your work–at least not more than ten years afterward. Take  Bonsal’s book opens on the eve of the Armistice and ends a little over a year later, with the Senate’s rejection of the Treaty. He worked alongside House, and later Wilson, through the preparations and initial sessions of the Conference. A veteran foreign correspondent fluent in a number of European tongues, he acted as an emissary to many of the other delegations and as a personal advisor to House and Wilson. He remained at the negotiating tables throughout most of the Conference, taking only a break of a few weeks to accompany South African General Jan Christian Smuts on a mission to Austria, Hungary, and Serbia in March and April 1919.

Bonsal’s book opens on the eve of the Armistice and ends a little over a year later, with the Senate’s rejection of the Treaty. He worked alongside House, and later Wilson, through the preparations and initial sessions of the Conference. A veteran foreign correspondent fluent in a number of European tongues, he acted as an emissary to many of the other delegations and as a personal advisor to House and Wilson. He remained at the negotiating tables throughout most of the Conference, taking only a break of a few weeks to accompany South African General Jan Christian Smuts on a mission to Austria, Hungary, and Serbia in March and April 1919.

“In the summer of 1963 I bought a 1941 Lincoln limousine in New York, so that I might be chauffeur in California to the few remaining dignitaries in my family,” William Saroyan explains at the start of

“In the summer of 1963 I bought a 1941 Lincoln limousine in New York, so that I might be chauffeur in California to the few remaining dignitaries in my family,” William Saroyan explains at the start of

Late in his time at the Crystal Palace, Harrington prepares a number of suggestions aimed at injecting a stronger sense of accountability into the company’s way of working, but then tosses them aside, recognizing they had no chance of being adopted. He had become, in his own words, “a thoroughly tamed playboy.” “Spiritually, my net worth was zero.” Only a lucky offer from Cary McWilliams, editor of The Nation, to write about his experiences finally offers him a way out. The article, and a grant from the

Late in his time at the Crystal Palace, Harrington prepares a number of suggestions aimed at injecting a stronger sense of accountability into the company’s way of working, but then tosses them aside, recognizing they had no chance of being adopted. He had become, in his own words, “a thoroughly tamed playboy.” “Spiritually, my net worth was zero.” Only a lucky offer from Cary McWilliams, editor of The Nation, to write about his experiences finally offers him a way out. The article, and a grant from the

At the same time as she starting placing stories, Brush also started getting more substantial newspaper reporting jobs, thanks in part to her husband and father-in-law’s connections. Most importantly, though she didn’t think so at the time, was a string of sports reporting assignments, which included the 1925 World Series, college football games, and the Jack Dempsey-Gene Tunney heavyweight boxing championship fight. “I wasn’t much good on the Dempsey-Tunney fight story,” she admits, but a few years later she recycled the material to good effect as the opening to her biggest-selling novel,

At the same time as she starting placing stories, Brush also started getting more substantial newspaper reporting jobs, thanks in part to her husband and father-in-law’s connections. Most importantly, though she didn’t think so at the time, was a string of sports reporting assignments, which included the 1925 World Series, college football games, and the Jack Dempsey-Gene Tunney heavyweight boxing championship fight. “I wasn’t much good on the Dempsey-Tunney fight story,” she admits, but a few years later she recycled the material to good effect as the opening to her biggest-selling novel,  Every writer who’s ever been featured on

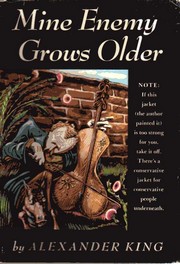

Every writer who’s ever been featured on  It was as an illustrator that King’s career finally took off. Throughout the 1920s, he was caught up in the convention-flounting wave of Mencken,

It was as an illustrator that King’s career finally took off. Throughout the 1920s, he was caught up in the convention-flounting wave of Mencken,  My theory is that King’s was a safe form of revolt. He mocked convention, but he didn’t exactly offer an alternative–nor did he suggest that people grab torches and set fire to police stations. He was like a

My theory is that King’s was a safe form of revolt. He mocked convention, but he didn’t exactly offer an alternative–nor did he suggest that people grab torches and set fire to police stations. He was like a  On the rare occasions when I’m back in the U.S., I always try to take time to stop by a public library and do some browsing through back issues of

On the rare occasions when I’m back in the U.S., I always try to take time to stop by a public library and do some browsing through back issues of

Paustovsky was a member of the Writer’s Union during years when it was probably impossible to work without cutting some bargain, committing some betrayal large or small, and ever so rarely we witness a tip of the hat to the prevailing dogma: “It was only in 1920 that I realized that there was no way other than the one chosen by my people. Then at once my heart felt easier.” Usually, these outbursts of Party faith are brief, awkward, and out of step with the rest of the story. The worst, a caricature of a

Paustovsky was a member of the Writer’s Union during years when it was probably impossible to work without cutting some bargain, committing some betrayal large or small, and ever so rarely we witness a tip of the hat to the prevailing dogma: “It was only in 1920 that I realized that there was no way other than the one chosen by my people. Then at once my heart felt easier.” Usually, these outbursts of Party faith are brief, awkward, and out of step with the rest of the story. The worst, a caricature of a